Richard Searling

Notes from the Passenger Seat of Northern Soul’s VanGuard – Seven Years on the Road with a white van man ‘legend’.

I first met Richard Searling as he struggled under the weight of his record boxes, at the entrance to the Va Va Northern Soul all-nighter in Bolton, when I was still at school. He was soon trying to groom me, with visits to a noisy North London establishment, to see some foreign geezers called Villa and Ardiles: But I wasn’t destined to be a Spurs fan.

In fact, I’ve since become a double Heretic:

A fekin’ Gooner?…

…Who believes the whole Northern Soul record box should’ve been remixed, re-modelled, re-recorded and reworked long before The Boss stepped in to give a few songwriters belated paydays.

To impress him with my knowledge of Northern tunes, I asked if he had a record I believed only Ian Levine owned (Rat Race by the Righteous Brothers Band, I think).

At subsequent all-nighters I wedged myself up against the Perspex sheets surrounding the Va Va’s DJ box and we became friends, thus beginning my seven year stint as Richard’s original co-pilot, in the first of many steeds; a white Escort van.

Like many a well-parented teen, I at first pretended to be a pill-head, to fit in with what I thought was expected of me by my peers. But dancing all night wasn’t intended for clean-livers/liver’s.

After my first ‘bluey’s’ (Drynamyl – normally 5mg Dexamphetamine, 32mg Amylobarbitone – in the days before I read great authors, I studied MIMS), there was no keeping me off the dance floor – all-night, all-day, all damn week.

The modernist Va Va’s hard-core pill-head all-nighter was short-lived, running as it did from April 1973 ’til August of the same year.

At the time, Richard’s day-job was at Global Records and whilst my memories of that first summer are sketchy, by the time Wigan opened in September, I too was a hardcore ‘soulie’, a regular at Blackpool Mecca’s Highland Room, had become acquainted with a clutch of jemmy-owning dodgy bastard’s – who over the coming years would fuel my weekend exploits – and had a girlfriend (and a handy box-room at her parents’) in Blackpool.

Come Wigan’s opening night, my name was on the Wigan Casino guest list (…though I never made it) and my stint in arguably the most privileged passenger seat in the history of Northern Soul was properly underway – only Ian Levine (who would’ve expected me to carry both record boxes: – poor Bernie!) and Colin Curtis’ passenger seats could compete, and I would not have exchanged mine for either.

We each tend to believe our Time of Living Dangerously was unique, though the collision of elements, resulting in the carnage of the real Northern Soul, was way more intoxicating and dangerous than most coming of age sagas; certainly the sterile variety made available on University campuses as part of your all-inclusive fee.

I should state now that whilst I turned into a bit of a rum ‘un, Richard (unless his book ‘Putting the Record Straight’ tells you otherwise) was a picture of Professionalism, and more often than not he’d finish his set at the Casino and drive home for some sleep, and although his mission was still to be fully defined, pharmaceuticals were not going to get in his way.

We’d be Back Together Again (a pun yet to be revealed) on the Sunday, at Blackpool Mecca, Manchester Ritz or some other all-dayer, before I’d be back in the passenger seat on our way home.

By Tuesday, I’d be a twitching mess with a rotting tongue (and feet, too, if I’d danced throughout in the same socks!). But I was never one to let that seat go wanting, and whilst Mr Professionalism was back on the decks at Carolines on Deansgate, Manchester, I’d be back on the dance floor, shuffling and sweating it out for Legend and The Faith.

Where we got to on the other weekdays depended on Richard’s DJ bookings, which could be anywhere from Wolverhampton to Barrow in Furness, and I even recall a brief midweek run at the Casino, which was a dank depressing dump without ‘phet and we bobbing, sweaty mongrels to give it relevance.

Then came the soul radio shows, on Radio Halom in Sheffield or Piccadilly Radio in Manchester, where I’d sit twiddling my thumbs or catch up on lost sleep in a corner of the studio.

When Richard got a job for RCA Records, at their Piccadilly offices (headed by the lovely Derek Brandwood), a new world opened up to me by proxy – we were soon off to gigs and after show parties, of RCA acts like Hall and Oats (previous pun now revealed), Sad Cafe and others, plus regular promotional stints at clubs like Pips and Placemate 7 with Andy Peebles (how on earth did he get to interview John Lennon? – networking skills have a lot to answer for) and the like.

One of my occasional roles was ‘buying’ RCA’s singles into the charts. I can’t recall the finer details of this dodgy practice, but, say, if a record shop ordered ten copies of a single, and they sold two, they couldn’t return the rest and had to enter the full ten copies ‘as sold’ (thus bumping up the numbers for a higher singles chart listing).

I’d get dropped off at record stores, whose sales were linked to the chart index, to buy copies of a given RCA single. The only reason this sticks in my memory is because of my acute embarrassment: not at scamming the chart system, but rather at the worry someone might spot me – a true Northern Soul disciple – buying mainstream chart shite, which I’d never have lived down, though one look at me would’ve confirmed to a wily sales person that something was amiss.

I also saw Joy Division on one of Richard’s scouting missions, when they performed at the Free Trade Hall as support for John Cooper Clark (they were shit) and I won’t even mention the Salford Jets at Swinton’s Duke of Welly pub.

And I was the only ecstatic person in that underground Preston club, when the Sex Pistols failed to show for a gig on a similar reconnoitre – punk had zero appeal for someone who loved a pulsing melody and preferred musicians who could actually play.

Initially, I was intimidated mingling with music industry types and players – so much ambition, so little passion and talent – particularly at RCA events and after-show parties: I mean, I was just a child-labourer from a shitty factory floor, with no head (nor inclination) for dizzying social heights, nor taste for the self-servers that populate it.

But to his credit, Richard was never embarrassed in the company of someone so uncomfortably out-of-synch with the pretentious movers and shakers of The Industry. If anything, it was the bullshitters to whom he was indifferent, and whilst open hostility was never in his Arsenal ( 🙂 I had to get it in somewhere!) he was never impressed by frills and fakes – they were merely jigsaw pieces in a business picture still forming in his head.

It was at one of these after-show ‘do’s’ that I asked Tricky how he dealt with big stars like Bowie: was he ever overawed?

His answer was roughly this: there’s always a door between you and them, and if you turn back, you’ll be turning back all your life – just walk through it and deal with whatever awaits.

I’ve since learned that this Confucian truism comes in a variety of translations, but it nevertheless had a profound effect and it is great advice for anyone, to get you to the point where no door fears you (except perhaps the one beyond the final curtain).

I used to think it was in these RCA days that Richard developed that sideways glance, coupled with the disarming smile, as a ruse to lull competitors and egos into a cosy foetal ball (he doesn’t need it as much now, atop of his own substantial pile).

But in truth, Richard Searling thought like – indeed was – a businessman from day one and he’d already seen the potential of local TV and radio as promotional tools for venues.

In fact, one of Dave Molloy’s mates used to tease him that he always wanted to be Alan Sugar, though a young-and-principled David Geffen would’ve been a better role model.

The instinct for business, the relentless work ethic, and the drive for…for…what, exactly?

A cheap answer occasionally suggested is money, but this isn’t true. Not strictly. Rather, with Richard, the perpetual motion of business is the yellow brick road, to the real businessman’s nirvana of control.

We former Apprentices (geddit?) cum-co-pilots are a small and devoted bunch: well, later ones more than me, I suppose, because when Richard and I became friends, the big adventure hadn’t properly started and neither of us had a pot to piss in (though the pot he didn’t have was worth more than mine).

Friendships founded on equal poverty sometimes foster a healthier equilibrium, along with a willingness to say what you mean – as opposed to what the boss might expect! – and from my end, that’s never abated.

Around four years ago I ran into one of my old school friends, Colin Markland, at Farnworth Cricket Club’s monthly Northern Soul Night, which has sadly now ceased.

I’d last seen him at Blackpool Mecca’s Highland Room back in the day (when I was in a hallucinogenic state…allegedly), and he asked rather perplexedly why a minority of Northern Soul folk don’t like Richard?

Envy is the cheap answer, though again only partially true.

In the main, the Northern Soul people I know are pretty accepting of others, though in later years – when the fake ‘love’ of speed wore off and freer spirits moved on to be defined by other things – it morphed into one of the most cult-like music movements on the planet, with a full pecking order of clergy to make rules for everyone else.

L Ron Hubbard reputedly stated that the real money is in religion and – as in many a cult and faux faith, which enforce dogma without spirituality – there are zealots aplenty.

As they’ve got(ten) older and crankier, these Zealots take occasional pot shots at Richard from the sidelines; for his undoubted dominance of the musical genre with festival-size events, and the construction of a Fiefdom from original Northern Soul building blocks.

Another muttered slight is that he’s made more money out of his venues than the artists ever did.

But so too have ‘phet dealers, successful rare vinyl sellers and most other promoters of Northern Soul, including that run-down ballroom in Wigan, which cashed in on a need and was hardly an egalitarian redistributor of the coin rolling through its front doors.

However, unlike most other NS promoters, Richard put money and much effort into soul’s Xpansion, and over the years he’s cross-promoted a wide range of soul artists and I would suggest that few have navigated the tricky tightrope, between a sincere love of black American music and personal business interests, as successfully as Richard Searling.

And without his relentless work ethic, innate determination to make ventures (and venues) work – particularly through the late 80’s and barren 90’s (King George’s Hall, Blackburn, being a good example) – and the contacts and money he’s made over the years, Northern Soul’s long goodbye may well have ended already.

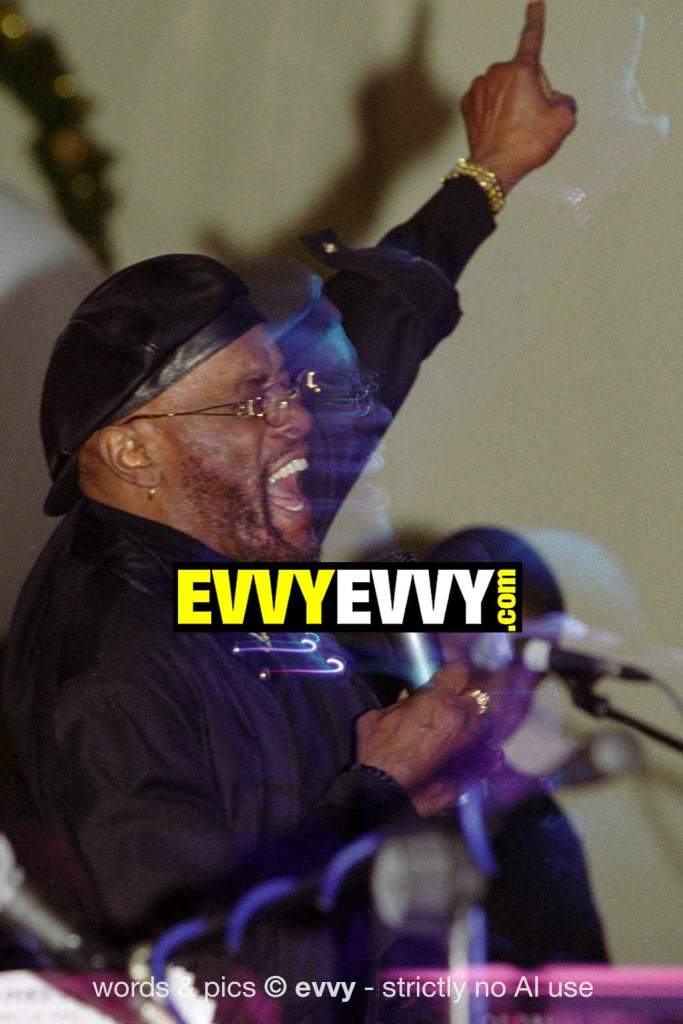

I certainly doubt we’d have danced in some of the world’s best ballrooms or had the opportunity to see the likes of Jean Carne, Bobby Womack, Dexter Wansell, Eddie Holman, Billy Paul, N’Dambi and many others perform, and his non-Northern events – like the sell-out January weekenders at Blackpool’s Hilton/Grand – are far more representative of soul music in general and the scope of his own musical tastes.

A further slight is that the Blackpool venues have an overly safe music policy and tend to play the same tracks on a permanent loop. But, again, this is a solid business decision – the world’s best ballrooms need to be paid for by loafers on sprung hardwood floor and bums on seats (if you can find one – grab a deck-chair from the Promenade) and the safe way to cater for the three-times-a-year crowd, who want to ‘listen to the memories’, is to play anthems from the middle of the road.

Of course this criticism is best answered at the Winter Gardens Soul Festival, which, with 7/8 rooms, is a fantastic event that pretty much caters for everyone – but then the trainspotters wouldn’t know how good it is, because they’re too busy arguing over spurious detail in the empty, shortening shadows.

I should highlight that I don’t do the grovelling advertorials that’ve been drowning out quality writing since the dawn of commercial interests, and nor am I Richard’s unsanctioned attack dog – apart from the occasional brief exchange, our shared narrative pretty much ceased in 1980.

But the reason for writing these essays is to achieve what to my eyes has never been done – to scythe through nostalgic platitudes, ditch the officially-sanctioned PR sermons to the faithful (which, to be blunt, usually serve Kev & Richard’s business interests better than the history books) and properly define what Northern Soul was, what it now is and what – if anything – the future holds.

And a realistic assessment of Richard’s role is essential to any full picture.

Yes, Richard tries to control as many elements of his business interests as he can – that comes with being a boss. But I reckon he’s made a pretty good play of the hand that was dealt him, and to my ears, much of the criticism muttered in the wings is unjustified, stamp-collector bollox.

No doubt some would’ve preferred him to be a commercial failure (like the recording artists they idolise), so they can gather around an empty dance floor, to draw dividing lines and bemoan The Faith’s lack of Limpieza de Sangre like the petty inquisitors they can’t quite help becoming, and discuss the obscure merits of dull, rarest-of-rare Z-Side offerings like Ronnie Scott pseuds… with two left feet in retiring dance-free slippers (Oops, sorry – I’m trying to curb my causticity but the talons came out and scratched my bloody keyboard).

I thought Robert Maxwell was a tw*t (I don’t take any Sugar, either), but he once made a remark that had me take note, to the effect that when you get lots of hands on the steering wheel, you end up going nowhere.

Irrespective of load-sharing partnerships, there was one Captain of Richard’s ship, and he only ever intended to sink or swim by his own efforts. And when you see 3000-plus people packed into the Blackpool Tower Ballroom or Winter Gardens, and not a space on the dance floor for the whole night, it might well be a victory of nostalgia and pantomime (‘He’s Behind You, Zealots,!’) over musical metamorphosis and invention, but it never fails to raise a pulse and a nod of appreciation, for the White Van Man ‘legend’ who mastered the business of putting on a bloody good show.

Although barely noticeable in those heady days of youth, there was always a degree of separation in our characters, which made it inevitable we’d be forever moving in different directions, for I was drawn by a star which shone in places that for Richard were blind spots: – a businessman’s treasure is an artist’s dead-weight.

Still, we made a good team back then, because neither of us were clingy, and I always understood – and was happy with – our unspoken roles: I was there to provide company, whilst Richard went about what otherwise would’ve been a lonelier ascent of Mount Northern, in exchange for a chauffeur and my Golden Ticket to the speed ball.

What started with a piece of music pretty much ended likewise: we were driving somewhere (Sheffield, I think) and Donna Washington’s Coming in for a Landing was playing on the car stereo, so the year was 1980.

Not one of Lamont Dozier’s best written efforts, and on that night the music seemed doubly hollow.

I think it was Simone Weil who warned that music could become ‘a background for daydreams’, which, like Caliban’s sweet airs, ‘give delight and hurt not’ as deeper realities slide by unnoticed.

By now my drug excess was a fading memory and I yearned for more than a gushing soundtrack, and a hitched ride on the back of someone else’s rising star.

In June of that year, I blagged a job teaching tennis in Bournemouth, and that was the end of my full-time Soulie adventure. Well, apart from expecting to swan-in on the guest list every so often and take my proxy-privileges for granted one more time (i can kiss those goodbye after the next piece – Northern Soul – A Future?).

However, I’m grateful to RCA records’ ‘tab’ for the opportunity of learning to dine out without using my fingers, and a controlled environment of egotists in which to sharpen fledgling faculties.

And I’ll always have love and respect for my first bezzie outside of school, for the memorable years we shared and my passenger seat at the eye of what was indeed a unique musical storm.

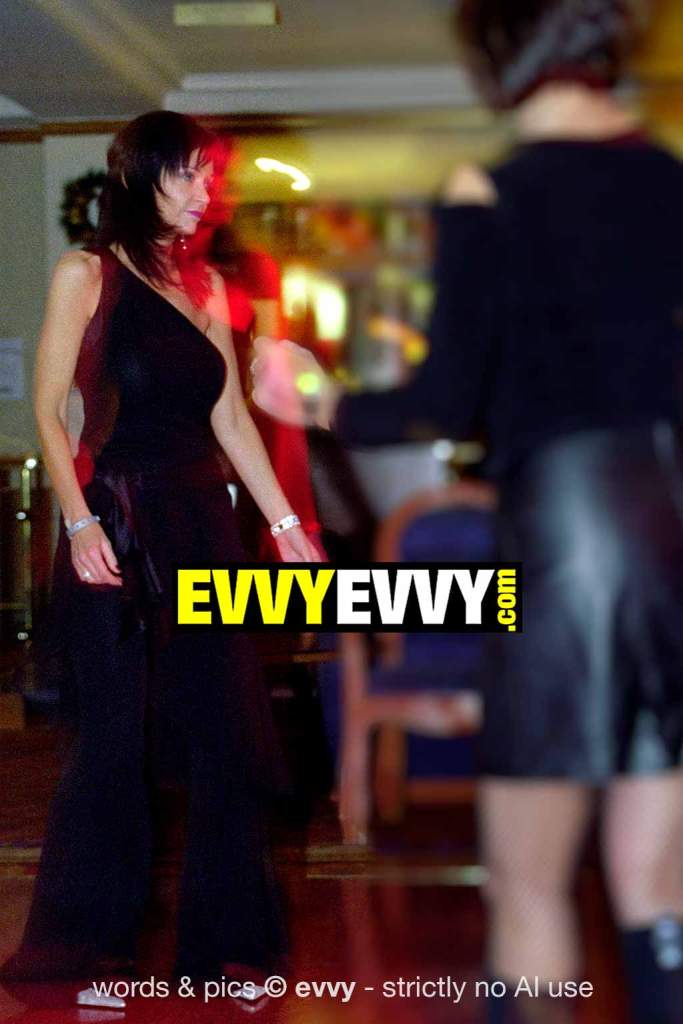

These days I see more of Mrs. Searling at her esteemed husband’s events and at a recent Tower Ballroom gig, as I yanked her towards the 5th Floor dance floor, one of her friends stepped in protectively.

‘Who are you?’ she quizzed sternly.

‘Oh this is Evvy,’ rescued Judith, ‘he was like one of the family through the Casino years,’ which was a nice thing to say.

Incapable of unquestioning fealty, and long-since estranged from the driving seat’s inner sanctum, though like family in the days before Northern Soul came full circle.

You must be logged in to post a comment.