Farnworth: A Past No Longer Present

Notes From the Real World

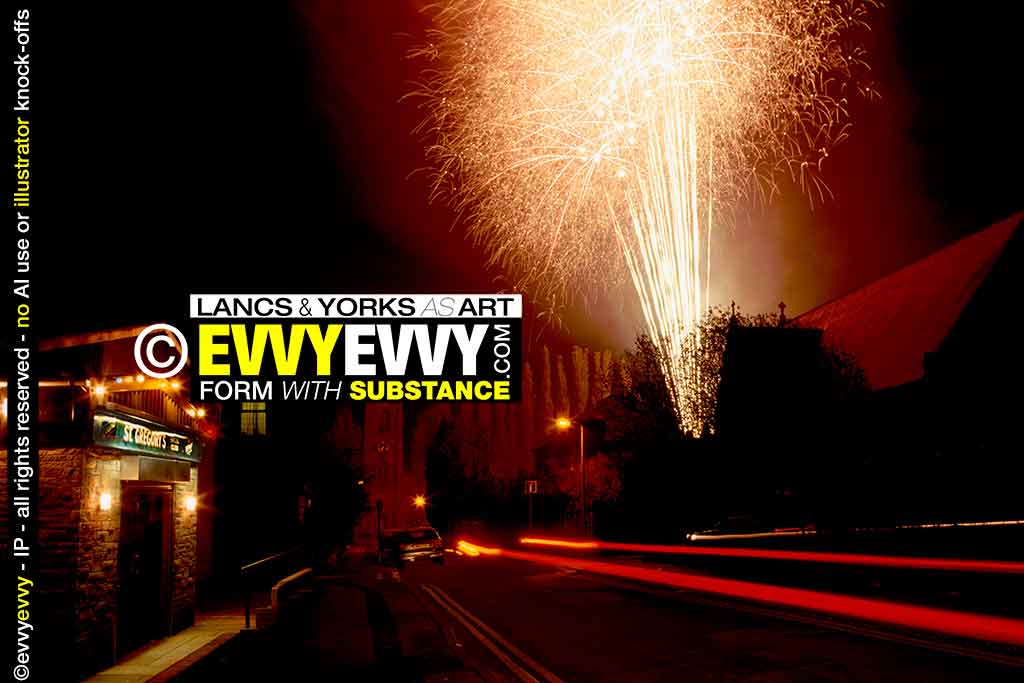

Farnworth and Kearsley is probably best known for housing television series Phoenix Nights. The real Phoenix Club, pictured, is called St. Gregory’s Social Club and it straddles the borderline of Farnworth and Kearsley, on the outskirts of Bolton.

I went to the Primary School that gave Saint Gregory’s club its name, so I know the terrain and when not long into High school I managed to put my hand (note that I tactfully say hand in preference to fist) through the glass in the club’s old main doors: I still have the scar on my camera trigger hand.

Bleached-white jeans and matching denim jacket were largely blood red by the time my dad bundled me into the passenger seat of his car, with my backside on a towel and my oozing hand wrapped in one. But he still made time to call at the shop on Peel Street for some polo mints, and he made me stuff the whole packet into my mouth at the hospital to lessen the smell of booze. They didn’t silence my drunken babble, though, and as they stitched me up I killed Rod Stewarts ‘Oh No Not My Baby’ at full pitch (and why do I remember that detail?).

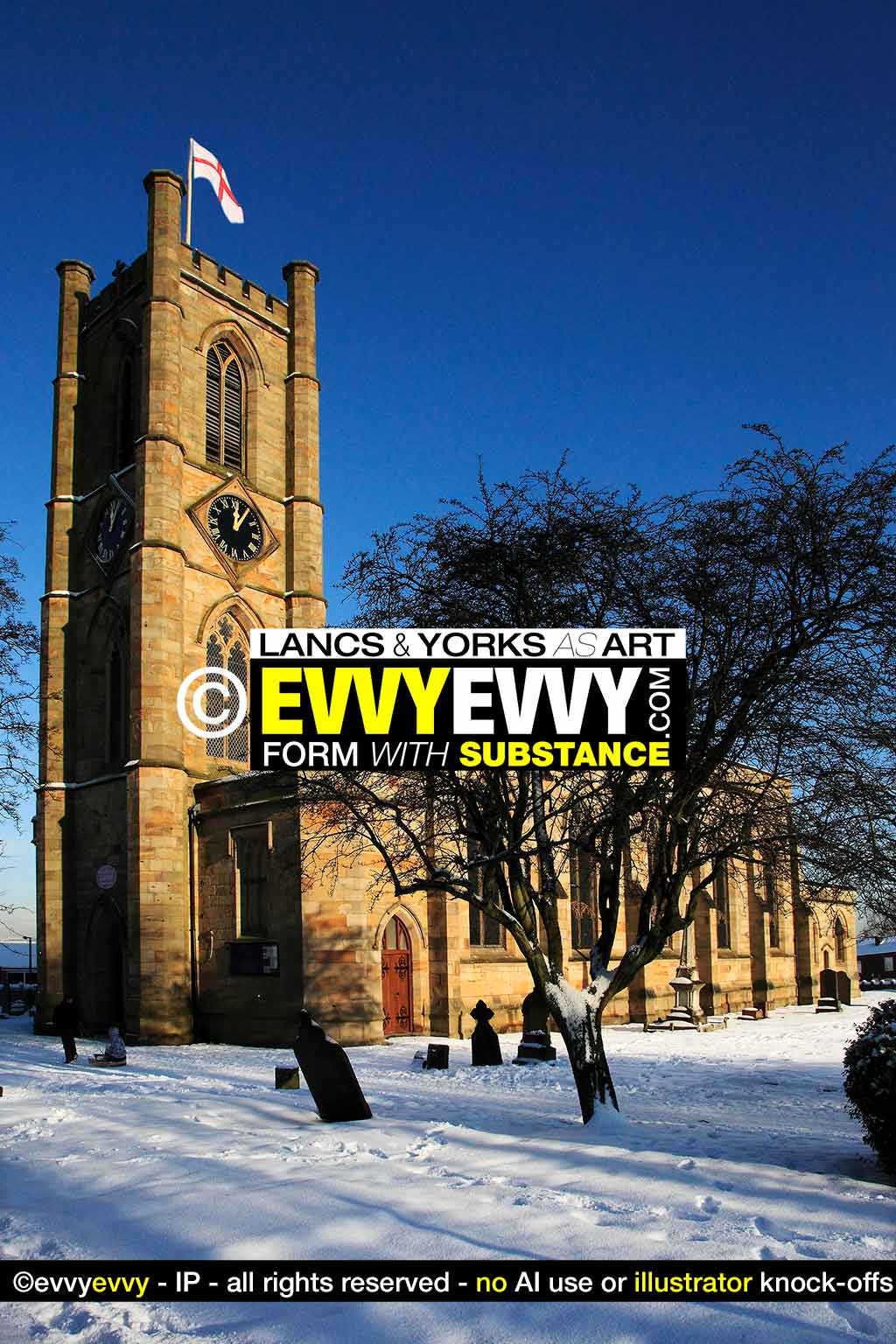

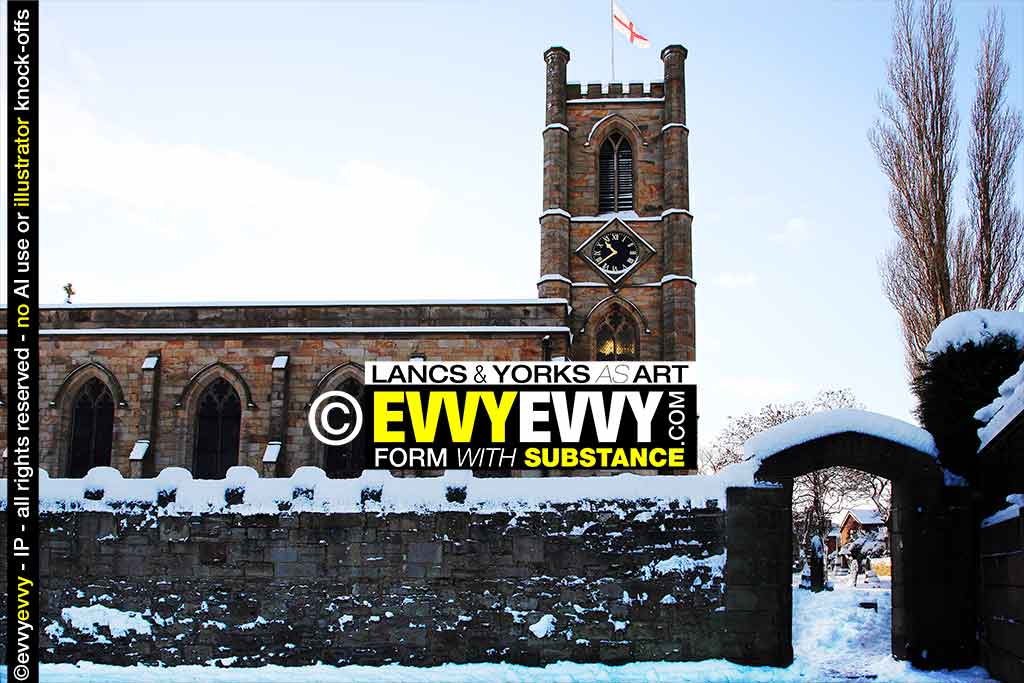

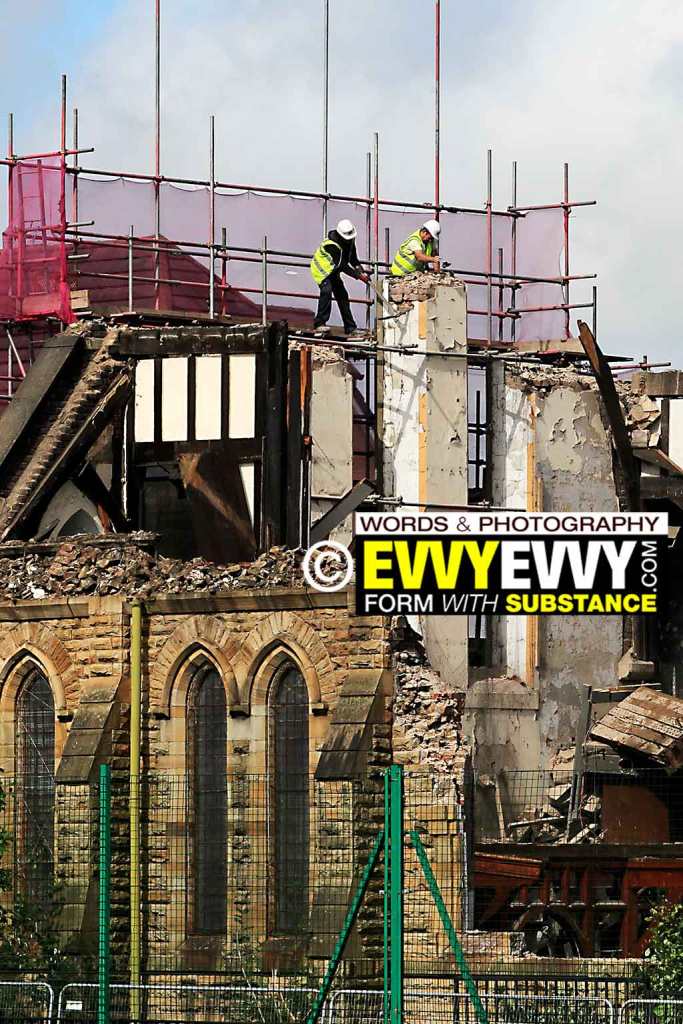

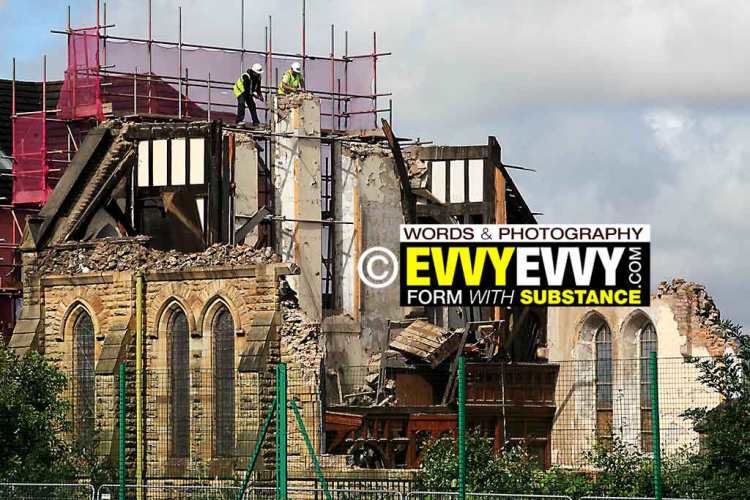

The original St. Gregory’s Club and School, which lived to the right of the sloping church roof in the photo (the church in the centre is Saint John’s), was the perfect shape for playtime football and the scene of May Day parades in my schooldays, when most boys wore a sky blue tie on an elastic band… and Father O’Dwyer would tug on the ears of anyone who didn’t and pull them across the playground.

The school and the old club buildings formed a gorgeous stone courtyard, which housed the original St Greg’s Club and was always home to a Youth Club, that turned out some self-taught County-standard table tennis players (when we weren’t competing to see who could pee highest up the outside wall: Ste Barber usually won).

I once suggested to Canon John Dale, who oversaw Saint Gregory’s Church demolition, that if more of us had paid into the Catholic coffers, saving it might’ve been possible: not so, I was informed, as the foundations had been crumbling for decades and whoever put the preservation order on the building just made it a much longer goodbye.

In reality—and of course for the right price—there aren’t many buildings that can’t be saved. But the once-proud church, no doubt erected partly as a middle finger to the Protestants down the road, in the days when Christian petty bigotry was still afoot (outside of you-know-where and you-know-where), was of little architectural value to the community at large without the adjoining school, which, if they’d been collectively restored, could’ve formed the cultural altarpiece of a Farnworth past no longer present.

In it’s place now lives a more functional school, and a bald patch marks the spot where the church and associated hall and presbytery once stood. As with the functional boxes that replaced perfectly serviceable terraced streets down the road, there may be fewer leaks in the school roof, but architectural gem it will never be.

Farnworth has been decimated by blinkered town planning (and that’s being polite) and over the last 30 or so years, virtually every piece of architectural heritage in this old cotton town has been levelled, and what some areas (and countries) have preserved for tourism and posterity, bright sparks here saw fit to demolish, making way for 3-4 supermarkets within a few hundred yards.

At least the hideous concrete shopping arcade (that replaced a tiled gem, complete with a gorgeous tiled baths to compare with Manchester’s Victoria baths) has been levelled.

But at what cost and to whose benefit?

The new-build apartments and commercial units raised as Farnworth Green, by Tim Heatley’s Capital Centric, are certainly an aesthetic improvement, though they weren’t offered for sale to locals.

Currently nearing capacity and occupied by many newly arrived people recruited to keep the NHS Titanic afloat, they’re a healthy improvement on the damp, musty ‘let’ that a hard-working Nigerian family I got to know were living in (850pcm on a two-bed terrace that’s never been damp-proofed – but that’s a whole new can of greed).

For a similar price you might get a one bed flat in the Farnworth Green development, which—without NHS backing—is way beyond what most working locals can afford—as are the business units—which suggests that gentrification is embedded into the high-price blueprint. And I’m guessing that high prices and 90% occupation would make the units easier to bundle into investment opportunities, for those wanting a better return than the 6% rates offered to the top tier (defo not the debanked people of Farnworth, then).

‘Housing is a service to be provided, not a commodity to be sold,’ is a Nye Bevan sentiment that Andy Burnham likes to quote, though I doubt it was used at the Farnworth Green photo op.

It would seem the only current benefit to locals is the spacious coffee shop, as a rich assortment of Farnworthians no longer have to suffer pound-shop Bolton to get a communal table and a good brew.

If you sit on one of the handful of benches at the centre of the Farnworth Green development, you may well be treated to a microcosm of the (post-civilisation?) breakdown of the authority (parent-child, teacher-pupil, which was synopsised in Netflix series Adolescence, though cause was only hinted at and counter-measures nowhere to be found) that’s been with us since Aristotle, and the nihilism it fosters is visible wherever you look.

On Summer days, the perma-tans of the long distance drinkers take up sun seats early outside Home Bargains, as the permanently prescribed shuffle noisily back-and-forth from Hollowood Chemists.

Kids on chipped ebikes aping balaclavad ‘delivery’ boys on Surrons (they’re not working for Uber Eats), pull 25mph+ wheelies through the Farnworth Green flower beds and weave in and out of shoppers along the sometimes pedestrianised Brackley Street (is it or is it not?) like slalom time-trialists, openly deriding the one PCSO who occasionally shows up to press PR palms, until the day the illegal transports whizzing past him hit a toddler or a Zimmer frame from Maxton House: too little too late will come the hindsight cry that everyone’s foresight saw clearly.

To be honest, I have sympathy with the ebike time-trialists—certainly, I have more in common with them than developers—for most of us were rudderless yoof once, and there is a primal thrill in travelling at speed… especially when there’s nowhere to go or much else to do. And if a town is going to give away prime land, on the meagre condition that investors make pretty that which previous generations of councillors have completely f*****d up, for it then to be sold on to goodness knows whom for a profit of goodness knows what, there is no connection or benefit for locals – especially kids with nothing to do – who can fast become second-class outsiders in their own ward. And that first wave of attitude, often aimed at that which you can neither be a part of nor a shareholder in, will always be exploited by tin-pot demagogues with a lust for limelight and power.

Even here (or especially here?) an occasional Tik Tokker, with spray tan thicker than a burka and lips transplanted from a duck-billed platypus, pulling ahead of her as if in a race with the rest of her face to reach some unseen destination, films her street-flounce, in the ‘influencers’ zombie-like quest to spread the ethical and intellectual cancer of Sociopathic Media, and the self-harm culture of cyclical narcissism, until—like Gadarene Swine herded by tech monsters’ quest for evermore ad-revenue—toppling lip-first into a rung of Dante’s Divine Comedy yet to be defined.

Unlike towns within the Ribble Valley and more salubrious parts of Lancashire, where NIMBY families are powerful and (like the best of battling Scousers – look up Liverpool’s campaign to save the Welsh Streets) organised enough to challenge local history’s demolition (wo)men, the folk of Farnworth and Kearsley get what they are given; historically by politicians and councillors who sometimes share the same heritage but who rarely live in the same straits, and more recently by Farnworth and Kearsley First, which lost much of its tenacity and intelligence, when the founder abandoned the ship he launched (for the very purpose of stopping community and architectural rot).

And I wouldn’t want to suggest that current local councillors are less sincere in wanting the best for their town. Certainly, they’re aware that Farnworth now has no bank branches, and a petition to open a banking hub has been offered.

But at best, this will provide only a short term solution because debanking entire towns – and eventually the nation – is a clear strategy.

So I thought a good alternative would be to write to Dave Fishwick and ask him how many Farnworth wage earners and pensioners it would take, to transfer their bank/savings accounts over to The Bank of Dave, for it to be worth his while opening a branch in Farnworth?

1000? 3000?

With a community campaign, I reckon its possible to achieve whatever figure he puts on it, and if we all encouraged five or ten family-and-friends to switch accounts, a mini revolution might be on the cards. Certainly worth an ask: anything to hit these ethical bankrupts in the only place they feel pain: so I did ask.

But, although they’ve applied to be a provider of everyday banking, they’ve yet to be granted the necessary licence (I wonder why). Bank of Dave 3?

In recent years I’ve made a point of drawing out cash and paying utility bills at counters, to do my bit to keep humans in a bank job. But the payment slips from my previous energy supplier weren’t accepted at pay machines within their bank, Barclays, which I don’t doubt was a tactic to coerce users into choosing the convenience of direct debit (after all, it was just as easy to make the slips machine-payable as not).

Barclays were the first to abandon Farnworth (so long ago I can barely recall) and in my experience, Barclays are the worst offenders in weaponising customer queues. For years they’ve been using fewer counters to make customers wait ever longer (…and longer……….and longer), which, when you think about it, is a clever-but-cynical way to force you to opt in to the cash-free convenience of online banking (not so convenient for you the next time banks go tits-up and you can’t get your cash out).

Having bottle-necked customers down to one counter, Bolton Barclays provided the most irritating experience, and at one point they told me at the counter that they were no longer accepting cash payments with utility slips! Many people would’ve given up and surrendered to the squeeze, but I was determined not to be beaten by these Unaccountables, so I made myself a nuisance at the branch in Manchester’s Saint Ann’s Square.

On telling one of the counter staff that they’d refused to accept my utility payments in Bolton, I was informed (by a manager,) that they were legally obliged to do so.

‘But why not just pay direct debit?’ I was asked.

‘Because I don’t like being manipulated into online banking so they can put you lot out of a job.

(S)he laughed and nodded.

‘That’s exactly what’s happening! Its just sad so few people even notice.’

Within weeks, the St Ann’s Square branch had been closed, so I doggedly joined an even bigger queue at Moseley Street.

This subtle nudging away from cash and towards the digit, ties nicely in with our governments increasing powers to look into people’s bank accounts: certainly cheaper than employing humans to police by consent, a concept being eroded for the cheaper model of policing by tech-stealth, as a topsy-turvy world gradually flips a presumption of innocence into an ‘I’ve got nothing to hide’ presumption of guilt that ends in Orwell or Kafka.

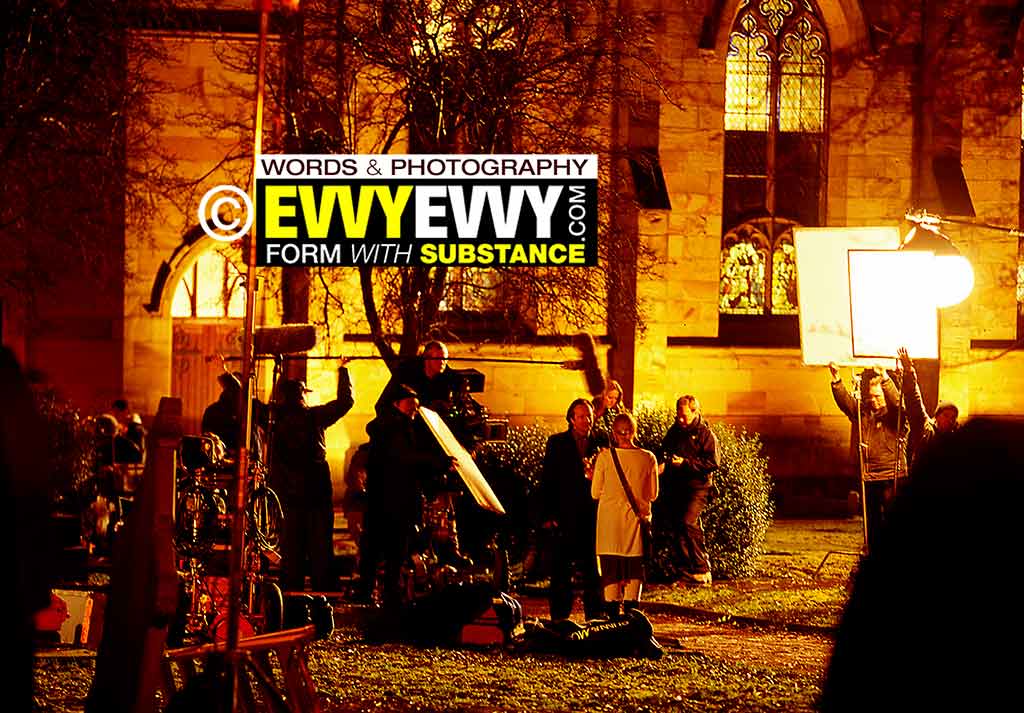

I first saw Phoenix Nights’ Peter Kay live at Manchester’s Frog and Bucket many moons ago, when ex-pupils of Mount Saint Joseph’s School noisily lined the balcony and floor. And his best role is undoubtedly that of stand-up comic, borrowing as he has from the people of Bolton and translating their collective ding dang do wit into cosy humour palatable for a middle-of-the-road audience.

Part of the charm of Phoenix Nights was the way it fed on (and pandered to) a sentimental Northern Englishness that was fast receding even then, and the cleanliness of its unreality arguably made it more popular with public schoolboys than locals.

But I always found the scripts of Phoenix Nights lumpy and thin because, like most television scriptwork, it is cobbled together by people who can learn basic formula but can’t really write, and consequently patchwork quilts are the TV norm and tapestries the exception. It was certainly immeasurably less funny than dry local realism, and the rich seam of Bolton humour was exhausted by the aptly titled Max and Paddy’s Road to Nowhere, and its doubtful leafy Heaton will inspire a reboot.

The last time I was in St. Greg’s Club was for the funeral of Arthur Davies, who was granddad to a family of kids I taught and stayed friends with. Owd Arthur was 95 when he died and in his wallet the family found only two keepsakes: a picture of his late wife and his 1958 cup final ticket when he, like many others from Bolton and Manchester, walked to Wembley Stadium because they couldn’t afford to get there any other way.

Active until the day he died, Arthur—like lots of Farnworthians—spent many years playing tennis on the public courts at Darley Park. In fact he got so good that another local, Bolton Wanderers legend Tommy Banks (who would buy his morning paper on Presto Street), one day asked Arthur if he’d teach him how to play. Arthur accepted the challenge, and one of Bolton Wanderers’ best-loved players subsequently learned how to play the game (for free) on a council-run public park… that’s now another run-down shithole, for want of some joined-up real-world thinking (what could’ve been maintained on the cheap would now need a fortune to resurrect).

It was on the same Darley Park that my younger self was introduced to both tennis and a future teacher. Beside the tennis courts was a neat putting green, for which you could hire putters and golf balls. But I was too lively for tip-tapping around the green and one day decided to try teeing off from a small mound of cut grass.

I can still see that ball sail high up-and-over the fence to the tennis courts, and disappear momentarily into the copious bosom of my future Maths teacher, Maureen Mullen. Years later, long after I’d left High School and she’d become a Deputy Head, we laughed when I admitted to being the guilty party. But the funny side was lost on me at the time, as half a dozen of the men—hardened working blokes ill-suited to pristine whites—chased me from the park and for half a mile up the road. But I had the good sense to lead the chasing pack away from my home, because parental responsibility was never absent in our house and if my Dad learned I’d hit someone with a golf ball, I would’ve been in serious bother.

It took a school trip (and Jimmy Connors) to fully reveal the potential of having community tennis courts on my doorstep, and it was on Darley Park where I taught myself how to play (and eventually how to teach) the only sport to ever captivate me.

At his funeral, the story was told of the day Arthur walked past St. Gregory’s Club while they were filming Phoenix Nights. One of the crew approached to ask if he’d like to earn some money as an extra and appear in the audience?

‘No thanks. Not my kind of humour,’ was his reply.

Now there’s a man of rare principal who would not sully himself for appearance money!

I hope rumours that money from the areas £20 million of level-up grants will pay for even more flower beds, for chipped ebikes and Sur-rons to churn up, prove to be false.

The lion’s share of any money would be better invested in desperately needed, non-profit alternatives to Darley Park, where apprentice ‘delivery’ drivers and serial self-harmers might be encouraged to have their energies shaped early, by knowledge and opportunities currently unavailable—both sporting and artistic.

But for facilities to provide lasting opportunities and inspire changes in attitude, a long-term plan of action is essential, and I know of nothing in Bureaucratic Bolton’s history to suggest a capacity for innovative action and joined-up thinking.

You must be logged in to post a comment.